Response #1

making things public

"From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik, or How to Make Things Public"

In: Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy

by Bruno Latour

In: Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy

by Bruno Latour

“We are asking from representation something it cannot possibly give, namely representation without any re-presentation, without any provisional assertions, without any imperfect proof, without any opaque layers of translations, transmissions, betrayals, without any complicated machinery of assembly, delegation, proof, argumentation, negotiation and conclusion” (Latour, 28).

- From the documentation of Making Things Public exhibition at ZKM. Please skip to 7:25 to 10:38 for Peter Weibel's explanation of Leviathan

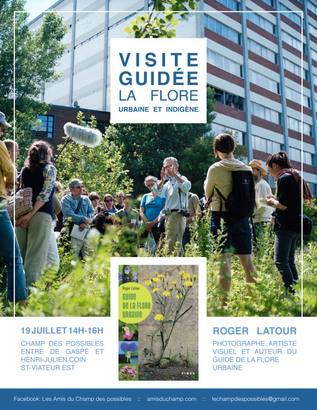

While reading Latour’s essay I was simultaneously studying the history of Champ Des Possibles and how the community proclaimed this unique space. Seen through Latour’s terms, the matter-of-concern in this case is a brownfield, a wasteland, that over some time had sprung into a diverse green space. For the surrounding neighborhoods it offered many things: a dog park, a productive space for biodiversity of plants, a park where many activities could take place, a unique place to study its upcoming and so on. For developers it offered a space for offices, condos, businesses and other projects alike. For the city the space had been long discussed as part of a plan to revitalize saint Viateur. Therefore the issue regarding the future of this space, this thing brought many people together because of the ways in which it divided them. Here the many processes concerning Champ Des Possibles offers a perfect example of Latour’s object-oriented-democracy. According to Latour “an object-oriented democracy should be concerned as much by the procedure to detect the relevant parties as to the methods to bring into the center of the debate, proof of what is to be debated” (Latour 8).

Who is to be concerned; and what is to be considered?

½ procedures ½ matters at issue

Who is to be concerned; and what is to be considered?

½ procedures ½ matters at issue

“We want to tackle the question of politics from the point of view of our own weaknesses instead of projecting them first onto the politician themselves... The cognitive deficiency of participants has been hidden for a long time because of the mental architecture of the dome in which the Body Politik was supposed to assemble.” (20) “We ourselves are so divided by so many contradictory attachments that

we have to assemble” (14).

The perspective from which the Friends of Field of Possibilities (public participants at the time) approached this problem is similar to that of Muff’s spatial agency. In order to identify the various functions of site, come up with a program and setup the initial project, the Mile End citizens committee assembled a series of meetings, discussions and public presentations with all parties concerned. Through this process the committee was able to shape a project and program that mobilized most of the demographic. As a result the assembly itself reached closure before going to the City. With majority of voices mobilized, the city finally recognized the various reasons and uses for preserving Field of Possibilities as a cultural site, and approved its program in 2009. The field has since been a project encouraging and attracting public participation and involvement of all who seek it, offering programs as diverse as: bee keeping, yoga, movie screenings, installations, composting issues, informative tours, talks, design and build sessions and much much more…

“Even infinitesimal innovation in the practical ways of representing an issue will make small – that is, huge – difference. Not for the fundamentalist but for the realists” (21).

In my opinion the struggle I mentioned above was one example of what Latour explains as Dingpolitik, but each ding has its own economies at scale. Concepts explored by Latour greatly shifted the way I look at problems and references to his work will continue throughout the journal, especially in the next reading by Rosalyn Deutsche, which shares a lot in common with Latour's Dingpolitik. In conclusion Making Things Public was an incredibly influential book along with Latour and Weibel’s essays and the many projects it exhibited.

we have to assemble” (14).

The perspective from which the Friends of Field of Possibilities (public participants at the time) approached this problem is similar to that of Muff’s spatial agency. In order to identify the various functions of site, come up with a program and setup the initial project, the Mile End citizens committee assembled a series of meetings, discussions and public presentations with all parties concerned. Through this process the committee was able to shape a project and program that mobilized most of the demographic. As a result the assembly itself reached closure before going to the City. With majority of voices mobilized, the city finally recognized the various reasons and uses for preserving Field of Possibilities as a cultural site, and approved its program in 2009. The field has since been a project encouraging and attracting public participation and involvement of all who seek it, offering programs as diverse as: bee keeping, yoga, movie screenings, installations, composting issues, informative tours, talks, design and build sessions and much much more…

“Even infinitesimal innovation in the practical ways of representing an issue will make small – that is, huge – difference. Not for the fundamentalist but for the realists” (21).

In my opinion the struggle I mentioned above was one example of what Latour explains as Dingpolitik, but each ding has its own economies at scale. Concepts explored by Latour greatly shifted the way I look at problems and references to his work will continue throughout the journal, especially in the next reading by Rosalyn Deutsche, which shares a lot in common with Latour's Dingpolitik. In conclusion Making Things Public was an incredibly influential book along with Latour and Weibel’s essays and the many projects it exhibited.

response #2

Public space | public sphere | public art

"Agoraphobia"

In: Evictions: Art & Spatial Politics

by Rosalyn Deutsche

"Art, Space & The Public Sphere(s):

Some Basic Observations on The Difficult Relation of Public Art, Urbanism and Political Theory"

Online @: EPICEP: European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

by Oliver Marchart

"Social space is produced and structured by conflicts. With this recognition, a democratic spatial politics begins" (Deutsche, xxiv).

In: Evictions: Art & Spatial Politics

by Rosalyn Deutsche

"Art, Space & The Public Sphere(s):

Some Basic Observations on The Difficult Relation of Public Art, Urbanism and Political Theory"

Online @: EPICEP: European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies

by Oliver Marchart

"Social space is produced and structured by conflicts. With this recognition, a democratic spatial politics begins" (Deutsche, xxiv).

public

By public space, who is the public and what space are we talking about? What role does the public sphere play for political art practices?

And finally in Deutsche's terms, what is public art and what role can it play in society?

Going back to the image of Leviathan and the concept of body-politik, we can see how the various needs and conflicting ideals of so many, is conceptualized to a unifying whole. As a result this form of representation, represents and misrepresents simultaneously, because a whole population cannot simply be represented through a political party, since the needs and opinions of so many will always need to be left out.

The role of the public sphere then is to formulate an opinion in order to achieve change through political action, where all citizens are assumed access. In reality, minorities and many unprivileged citizens are left out. As a result when we hear of various successes of the public realm, many are left outside of this normative definition of public. For example, we hear about revitalization of social spaces such as Toronto's Regent Park, Montreal's Lachine Canal, Griffintown, or as per Deutsche's example of the triumph of a public space' over Jackson's park in New York's Greenwich Village, where through what is considered to be the public's will, the city performs 'cleansing' of spaces, sometimes by evicting the homeless, or closing down of 'unorderly' sites that challenge the norm and expose social and political conflicts within the framework of a democratic society.

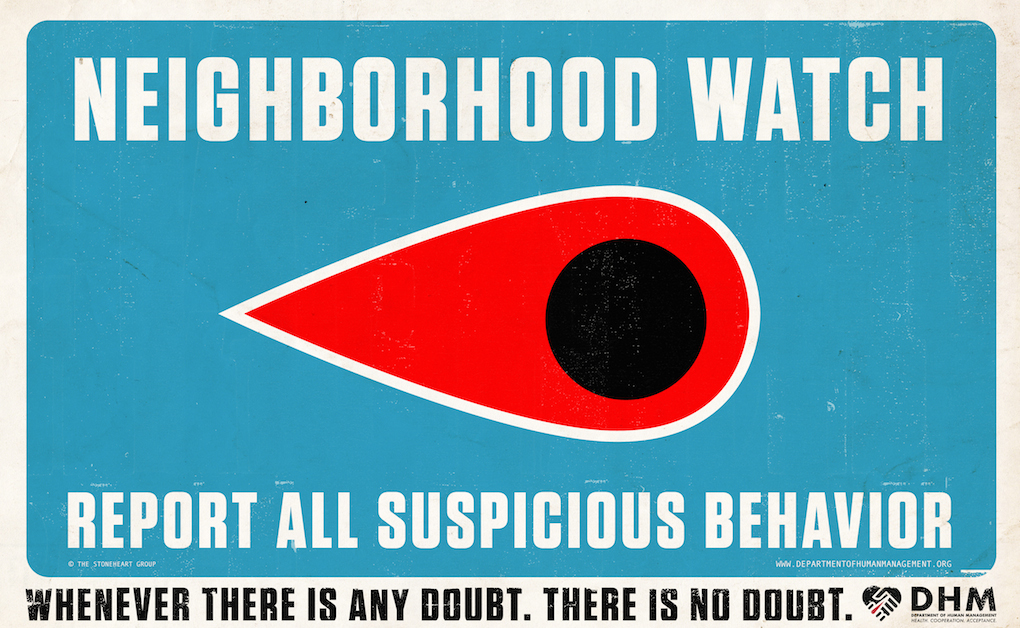

Even though it is most certainly over-the-top, the comedy movie Hot Fuzz depicts such conflicts in a small-town, where all persons not belonging to the village, are ‘strangers’ and suspect. In the fictional village of Sandford, fundamentalist perceptions of what is considered 'normal' calls for the motivation to eradicate or replace the “unwanted” or 'others' for what the characters repeatedly mention as

THE GREATER GOOD...

By public space, who is the public and what space are we talking about? What role does the public sphere play for political art practices?

And finally in Deutsche's terms, what is public art and what role can it play in society?

Going back to the image of Leviathan and the concept of body-politik, we can see how the various needs and conflicting ideals of so many, is conceptualized to a unifying whole. As a result this form of representation, represents and misrepresents simultaneously, because a whole population cannot simply be represented through a political party, since the needs and opinions of so many will always need to be left out.

The role of the public sphere then is to formulate an opinion in order to achieve change through political action, where all citizens are assumed access. In reality, minorities and many unprivileged citizens are left out. As a result when we hear of various successes of the public realm, many are left outside of this normative definition of public. For example, we hear about revitalization of social spaces such as Toronto's Regent Park, Montreal's Lachine Canal, Griffintown, or as per Deutsche's example of the triumph of a public space' over Jackson's park in New York's Greenwich Village, where through what is considered to be the public's will, the city performs 'cleansing' of spaces, sometimes by evicting the homeless, or closing down of 'unorderly' sites that challenge the norm and expose social and political conflicts within the framework of a democratic society.

Even though it is most certainly over-the-top, the comedy movie Hot Fuzz depicts such conflicts in a small-town, where all persons not belonging to the village, are ‘strangers’ and suspect. In the fictional village of Sandford, fundamentalist perceptions of what is considered 'normal' calls for the motivation to eradicate or replace the “unwanted” or 'others' for what the characters repeatedly mention as

THE GREATER GOOD...

- A Short excerpt from the movie Hot Fuzz (2007)

While the movie might make a good laugh, the visible differences and conflicts within society should never be broken down to forces of good or evil. It should rather be contingent vs. absolute forces, or matters-of-concerns vs. matters-of-facts, because as Deutsche describes:

"Urban space is the product of conflict. This is so in several, incommensurable senses. In the first place, the lack of absolute social foundation - the 'disappearance of the markers of certainty' - makes conflict an ineradicable feature of all social space. Second, the unitary image of urban space constructed in conservative discourse is itself produced through division, constituted through the creation of an exterior. The perception of a coherent space cannot be separated from a sense of what threatens the space, of what it would like to exclude.

Finally, urban space is produced by specific socioeconomic conflicts that should not simply be accepted, either wholeheartedly or regretfully, as evidence of the inevitability of conflict but, rather, politicized - opened to contestation as social and therefore mutable relations of oppression"

(Deutsche, 278).

Going back to my first post on Champ-Des-Possibles, where the Mile End community proclaimed the park as public space, I was very surprised to see similar problems of representation were still evident. During my visit I got the chance to speak to a couple of young residents active in the area and listened to their concerns about homeless people ruining the atmosphere of the space by sleeping there at night. This made me realize that even though the citizens committee was very empowering in assembling the residents, there were still certain citizens that were left outside of the process and image of this community. Namely the homeless, where their presence can be frowned upon by residents who assume privilege over this space. Therefore conflicts are evident throughout all spaces in society, and where they show up, can be in no 'space' at all...

space

"Lefort's public sphere is precisely not a space, but rather, in the final analysis, belongs to the order of temporality, namely to the order of conflict. Lefort's public sphere is thus ultimately not an ontic location but rather an ontological principle - dislocation. The model of radical and plural democracy is not concerned with the substantial consensual standardization of space, i.e. finding consensus, but rather with its conflictual opening. It is about avoiding precisely the occupation of the empty space of power, the permanent creation of closed space" (Marchart, SOURCE).

art

According to Lefortian definitions of public sphere and public space, what is the role of public art? Or more specifically art in the public interest: social interventionism?

In this part of the journal I will quote what Rosalyn Deutsche refers to as the final question. Then I will make my response to it in the next section of the journal, by taking the works and ideas of Krzysztof Wodiczko as an example.

While the movie might make a good laugh, the visible differences and conflicts within society should never be broken down to forces of good or evil. It should rather be contingent vs. absolute forces, or matters-of-concerns vs. matters-of-facts, because as Deutsche describes:

"Urban space is the product of conflict. This is so in several, incommensurable senses. In the first place, the lack of absolute social foundation - the 'disappearance of the markers of certainty' - makes conflict an ineradicable feature of all social space. Second, the unitary image of urban space constructed in conservative discourse is itself produced through division, constituted through the creation of an exterior. The perception of a coherent space cannot be separated from a sense of what threatens the space, of what it would like to exclude.

Finally, urban space is produced by specific socioeconomic conflicts that should not simply be accepted, either wholeheartedly or regretfully, as evidence of the inevitability of conflict but, rather, politicized - opened to contestation as social and therefore mutable relations of oppression"

(Deutsche, 278).

Going back to my first post on Champ-Des-Possibles, where the Mile End community proclaimed the park as public space, I was very surprised to see similar problems of representation were still evident. During my visit I got the chance to speak to a couple of young residents active in the area and listened to their concerns about homeless people ruining the atmosphere of the space by sleeping there at night. This made me realize that even though the citizens committee was very empowering in assembling the residents, there were still certain citizens that were left outside of the process and image of this community. Namely the homeless, where their presence can be frowned upon by residents who assume privilege over this space. Therefore conflicts are evident throughout all spaces in society, and where they show up, can be in no 'space' at all...

space

"Lefort's public sphere is precisely not a space, but rather, in the final analysis, belongs to the order of temporality, namely to the order of conflict. Lefort's public sphere is thus ultimately not an ontic location but rather an ontological principle - dislocation. The model of radical and plural democracy is not concerned with the substantial consensual standardization of space, i.e. finding consensus, but rather with its conflictual opening. It is about avoiding precisely the occupation of the empty space of power, the permanent creation of closed space" (Marchart, SOURCE).

art

According to Lefortian definitions of public sphere and public space, what is the role of public art? Or more specifically art in the public interest: social interventionism?

In this part of the journal I will quote what Rosalyn Deutsche refers to as the final question. Then I will make my response to it in the next section of the journal, by taking the works and ideas of Krzysztof Wodiczko as an example.

"How can art develop the experience of being public, by aiding the appearance of others, while also making visible the limits they face places on the success of any representation, limits that are the condition of appearance" (Deutsche, 14:50).

- From a collection of video recordings of day 2 of Tate Modern’s Making Public series. The event centers on how publicness emerges in art and art writing (SOURCE)

Response #3

Krzysztof Wodiczko

"Krzysztof Wodiczko: Public Space: Commodity or Culture"

In Streetnotes 20: URBAN FEEL. Spring 2010

by Louis Ascher

"Designing The City of Strangers"

As part of Wodiczko's lectures in Harvard University, 1997

by Krzysztof Wodiczko

Since the 1970s, Wodiczko has been exposing conflicts within society that hide behind seemingly innocent spaces and architectures of the city. Most of his interventions involve a series of projections that seek to reveal the layers of power and control that political, cultural, social, and economic institutions attach themselves to spaces in the city.

In Streetnotes 20: URBAN FEEL. Spring 2010

by Louis Ascher

"Designing The City of Strangers"

As part of Wodiczko's lectures in Harvard University, 1997

by Krzysztof Wodiczko

Since the 1970s, Wodiczko has been exposing conflicts within society that hide behind seemingly innocent spaces and architectures of the city. Most of his interventions involve a series of projections that seek to reveal the layers of power and control that political, cultural, social, and economic institutions attach themselves to spaces in the city.

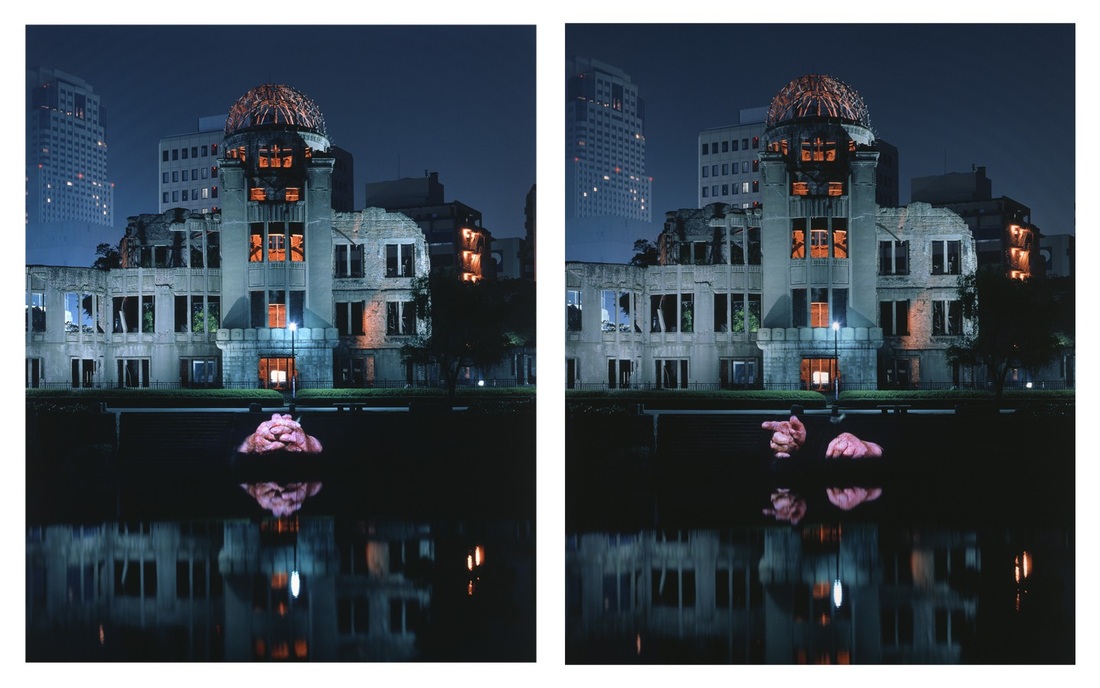

In "Public Projection, Hiroshima, August 1999" Wodiczko enables a dome, that was the only witness to the destruction around it, to create a dialogue about the Hiroshima bombing of 1945. He does this through a series of interviews with various citizens whose hands anthropomorphizes the dome. In one specific interview shown by Deutsche in Tate Modern's Making Public Series, a 60 year old survivor explains her frustration when she simply couldn't speak a word in a town's meeting when the general was speaking of the advantages of the atomic bomb and how it shortened the war and kept the peace. All the while she said, her hands where shaking mad, but she could not utter a single word.

"The Hiroshima projection developes the viewer’s experience of being public by facilitating the appearance of the face of the other." (Deutche, 16:20)

My understanding of this is that appearances (going back to the problem of representation), set limits to our understanding, set limits to accessing full knowledge about a topic. So these faces are faces that speak out, they are faces that through the Hiroshima projection experience demand proper representation. Faces that by their appearance uncontrollably feel marginalized and left out (I'm thinking about the experience of the old lady in the meeting, or the reason behind 'the code of silence' in Boston).

Wodiczko's work allows the viewer to realize these non-visible problems of representation, non-visible because they are the problems that are hidden behind the headlines, that are hidden behind what we are normally presented as matters-of-facts. He creates an opportunity for the suppressed voices of citizens to be heard, and orchestrates an experience for the viewers to sense the conflicts hidden behind these dialogues and testimonies.

Foucault describes this process as "fearless public speaking" (source)

"The Hiroshima projection developes the viewer’s experience of being public by facilitating the appearance of the face of the other." (Deutche, 16:20)

My understanding of this is that appearances (going back to the problem of representation), set limits to our understanding, set limits to accessing full knowledge about a topic. So these faces are faces that speak out, they are faces that through the Hiroshima projection experience demand proper representation. Faces that by their appearance uncontrollably feel marginalized and left out (I'm thinking about the experience of the old lady in the meeting, or the reason behind 'the code of silence' in Boston).

Wodiczko's work allows the viewer to realize these non-visible problems of representation, non-visible because they are the problems that are hidden behind the headlines, that are hidden behind what we are normally presented as matters-of-facts. He creates an opportunity for the suppressed voices of citizens to be heard, and orchestrates an experience for the viewers to sense the conflicts hidden behind these dialogues and testimonies.

Foucault describes this process as "fearless public speaking" (source)

By situating a homeless as neighbor in front of the Trump Towers (as shown above) and in other spaces in the city, Wodiczko disrupts the suppressed and accepted realities of our everyday life, or as he would describe it 'our dominant culture of privilege'. The vehicle creates a sense of discomfort by making people confront the conflict directly, and it is from this sense and experience, that he tries to unveil the human cost behind our 'culture of privilege'.

“Silence and invisibility are the biggest enemies of democracy.

If you cannot speak, none of your other constitutional rights can be exercised” (Wodiczko News Office Massachusetts Institute of Technology On-line Bulletin)

If you cannot speak, none of your other constitutional rights can be exercised” (Wodiczko News Office Massachusetts Institute of Technology On-line Bulletin)

Response #4

Waste assessment | waste management

"Drosscape"

In: The Landscape Urbanism Reader

by Alan Berger

waste & waste landscapes as an outcome of two major factors:

1 Urbanization &

- urban sprawl. "rapid urbanization of newer city areas (the periphery)"

(Berger 200)

2 Deindustrialization

- spaces in the older city areas (the city core) left behind "after economic and

production regimes have ended", (ex. along Lachine Canal, where

manufacturing is decentralized, moved abroad or to suburbs.)

In: The Landscape Urbanism Reader

by Alan Berger

waste & waste landscapes as an outcome of two major factors:

1 Urbanization &

- urban sprawl. "rapid urbanization of newer city areas (the periphery)"

(Berger 200)

2 Deindustrialization

- spaces in the older city areas (the city core) left behind "after economic and

production regimes have ended", (ex. along Lachine Canal, where

manufacturing is decentralized, moved abroad or to suburbs.)

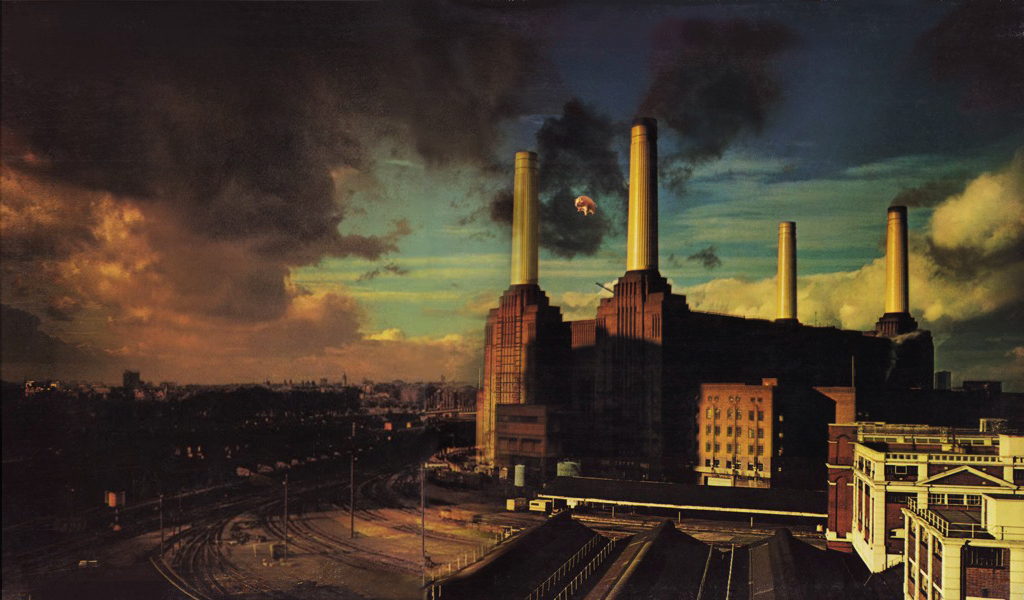

Battersea Power Station - a famous power plant in London, England (here on the cover of Pink FLoyd's album 'Animals') that has been out of operation since 1983. It is now being renovated as part of a massive redevelopment plan to supply renewable energy, housing, offices and parks.

In order to avoid nostalgia, and be creatively constructive, Berger proposes an alternative way of thinking about waste: waste as a result of natural processes; as a product of human growth and human progress. By taking this positive and pragmatic approach we can look at landscapes of waste, as spaces that are left for the city to enjoy and reuse. Berger also proposes not to use the term 'post-industrial' that is most commonly associated with landscapes of waste, because 'post-industrial' "defines [a space] in terms of the past rather than as part of an ongoing industrial process that forms other parts of the city" (200).

In coming up with various solutions to these spaces of waste, we once again turn to Latour's matter-of-concern approach. In Latour's way of dealing with various processes, we take a multidisciplinary approach where the meanings of scientific and political representations, merge into one (Latour, 214). One of the major problems arises when private corporations take over these lands (since by being a site of waste, their price is heavily reduced), and they start massive development projects with no regards to cultural and political implications of their intervention within various sites. These projects are not an appropriate and sustainable response to waste landscapes because they can further extend the problems of waste.

I will briefly take Lachine Canal and Girffintown as an area of focus. The canal during the 19th and early 20th century, while being a site of intense labor, social injustice and class struggles, brought many neighborhoods together, both socially and politically. This is because the site was more active amongst citizens. However, now this social space is jeopardized through private condo developments in the area.

In order to avoid nostalgia, and be creatively constructive, Berger proposes an alternative way of thinking about waste: waste as a result of natural processes; as a product of human growth and human progress. By taking this positive and pragmatic approach we can look at landscapes of waste, as spaces that are left for the city to enjoy and reuse. Berger also proposes not to use the term 'post-industrial' that is most commonly associated with landscapes of waste, because 'post-industrial' "defines [a space] in terms of the past rather than as part of an ongoing industrial process that forms other parts of the city" (200).

In coming up with various solutions to these spaces of waste, we once again turn to Latour's matter-of-concern approach. In Latour's way of dealing with various processes, we take a multidisciplinary approach where the meanings of scientific and political representations, merge into one (Latour, 214). One of the major problems arises when private corporations take over these lands (since by being a site of waste, their price is heavily reduced), and they start massive development projects with no regards to cultural and political implications of their intervention within various sites. These projects are not an appropriate and sustainable response to waste landscapes because they can further extend the problems of waste.

I will briefly take Lachine Canal and Girffintown as an area of focus. The canal during the 19th and early 20th century, while being a site of intense labor, social injustice and class struggles, brought many neighborhoods together, both socially and politically. This is because the site was more active amongst citizens. However, now this social space is jeopardized through private condo developments in the area.

Gentrification of sites such as Lachine canal can become problematic when development projects like Myst (as shown above), become heavily concentrated on a specific site, and build without any regard to the site’s history and identity. As a result, an area once socially active and public, can become privatized, limiting access by taking over a whole area. Therefore preserving cultural sites, and respecting the various demographics within wastelands becomes a crucial concern when reusing or developing on old sites.

Allez Up - Located in the Southwest boroughs of Montreal and along Lachine Canal, this rock climbing center is the beautifully renovated old Redpath sugar refinery silos.

The space affords interesting challenges for climbers, such as the inside of the silos, where you can climb up the whole structure. "Developing the abandoned silos into a rock-climbing gym is a unique way to maximize the enormous potential of these historic vestiges from Montreal’s industrial past."

Allez Up - Located in the Southwest boroughs of Montreal and along Lachine Canal, this rock climbing center is the beautifully renovated old Redpath sugar refinery silos.

The space affords interesting challenges for climbers, such as the inside of the silos, where you can climb up the whole structure. "Developing the abandoned silos into a rock-climbing gym is a unique way to maximize the enormous potential of these historic vestiges from Montreal’s industrial past."

|

In many cases preserving the site, rather than taking it over, is the main issue. In the case of the canal, the site to preserve is both a cultural and social one, but in the case of brownfield sites, they need to be preserved specifically because they are contaminated; they need to be preserved because their "abandonment may bring favorable ecological surprises. Ecologist often find much more diverse ecological environments in contaminated sites than in native landscapes that surround them... Brownfield sites [Such as Champ-des-Possibles or the site across Avenue 32] offer a viable platform from which to study urban ecology while performing reclamation techniques. These sites have the potential to accommodate new landscape design practices that concurrently clean up contamination during redevelopment, or more notably where reclamation becomes integral to the final design process and form" (Berger 209).

|

I will very go over a number of projects that I was thinking about in relation to ideas and concepts, explored by Alan Berger.

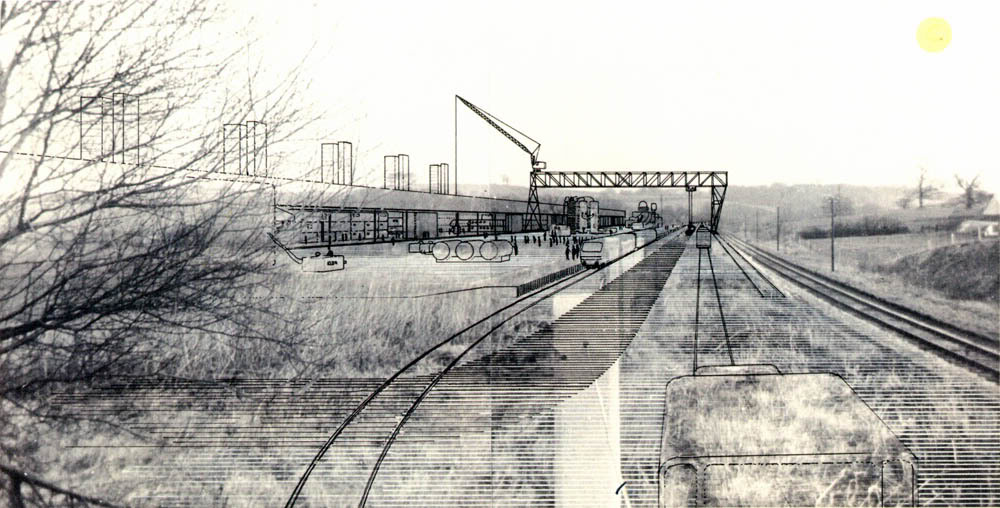

The first project is Cedric Price's "Potteries Thinkbelt" and the second one, Filipe Balestra & Sara Göransson's incremental housing strategy. Both these projects bear in mind the extend of which waste is concerned within various processes in our society, and they both implement an adaptable sustainable strategy in response to different spaces of waste. Price's ideas mostly revolves around the problems of deindustrialization, while the other on urbanization.

The first project is Cedric Price's "Potteries Thinkbelt" and the second one, Filipe Balestra & Sara Göransson's incremental housing strategy. Both these projects bear in mind the extend of which waste is concerned within various processes in our society, and they both implement an adaptable sustainable strategy in response to different spaces of waste. Price's ideas mostly revolves around the problems of deindustrialization, while the other on urbanization.

|

Cedric Price's Potteries Thinkbelt - I'm referring to Cedric Price for his incredible ideas of designing for adaptability, and his interests in movement, mobility and sustainability. He envisioned reconversion of industrial sites early on, that later became a trend in design practices. Potteries Thinkbelt although never realized, used the industrial infrastructure of the North Staffordshire Potteries and turned it into a new kind of High-Tech University. Over the course of 19th to 20th century the site had deteriorated, and due to economic crisis finally left the area devastated. Cedric came up with the project to bring it life once a again, mixing education, mobility, and production within the proposed space. More importantly he "acknowledged that architecture was too slow in solving immediate problems and for this reason he opposed the development of permanent buildings that were limited for a particular function. Instead, he stressed that buildings needed to be constructed for adaptability because of the unpredictability of the future use of these spaces. Potteries Thinkbelt emphasis Price’s “preference for dismantling architecture and making it disappear into unconventional systems.” The Thinkbelt not only predated the vast reconversion of industrial sites; [it is also a] paradigmatic example of an urban environment whose values, forms, and ideology resonate with the great transformations that have affected the global economy since the late 1970s" [source].

|

Incremental Housing Strategy in India by Filipe Balestra & Sara Göransson - In this project the designers came up with a strategy that was "way better than just designing or constructing, [they developed] strategies together with communities to achieve housing solutions that not only address today´s necessities, but that can also be extended over time as families grow, by themselves and without architects... The strategy uses the existing urban formations as starting point for development. Organic patterns that have evolved during time are preserved and existing social networks are respected. Neighbors remain neighbors, local remains local" [source].

Since this response has become quite lengthy, I will leave the rest of the examples without much description. I hope the following projects' relevance to the essay is clear. If you have the time and wish to explore further, please click on the link provided.

Westergasfabriek Culture Park - is a former gasworks in Amsterdam, now used as a cultural venue.

Westergasfabriek Culture Park - is a former gasworks in Amsterdam, now used as a cultural venue.

Wunderland Kalkar - is an unused nuclear power plant (since Germany switched to renewable energy sources) that is converted into an amusement park.

The Heidelberg Project - is an outdoor project and a community in Detroit, that has been active for 25 years. It is part of a political protest and struggle "to improve the lives of people and neighborhoods through art... [Their] mission is to inspire people to appreciate and use artistic expression to enrich their lives and to improve the social and economic health of their greater community." The project "uses everyday, discarded objects to create a two block area full of color, symbolism, and intrigue."

Growing Underground Project - is a company that grows herbs in former World War Two air raid shelters under south London, integrating farming into the urban environment.

response #5

getting back to the wrong nature

"The Trouble with Wilderness: or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature"

In: Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature

by William Cronon

“My criticism in this essay is not directed at wild nature per se, or even at efforts to set aside large tracts of wild land, but rather at the specific habits of thinking that flow from this complex cultural construction called wilderness.” (Cronon 12)

In: Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature

by William Cronon

“My criticism in this essay is not directed at wild nature per se, or even at efforts to set aside large tracts of wild land, but rather at the specific habits of thinking that flow from this complex cultural construction called wilderness.” (Cronon 12)

here's a slightly different view on nature

- An excerpt from a documentary series on nature by Werner Herzog

We need to understand the implications, problems and risks of what it means to view nature as something outside or rather separate from our actual place within it. Viewing nature through a lens of detachment becomes extremely problematic, as things seen at a distance have the dangerous potential to become abstract. When we remove ourselves from nature, we simultaneously romanticize it. In this romanticization nature becomes a commodity in constant battle with culture.

By looking at the sublime and the frontier movements, Cronin studies how, in the last 250 years our view of wilderness and nature have transformed from something ‘deserted’ and ‘savage’, to something godly, sacred and exotic. In these ways nature is seen as a cultural invention. This way of thinking exoticizes nature, implanting an ‘untouched’ image of wilderness into the Western Consciousness, while also propagating the idea that nature has died as a result of human interference. This view gets in our way of thinking progressively about a world where humans can strive towards a nature we are part of.

Unfortunately this ideology has been carried forward into sustainability practices, with new environmental initiatives springing from the romanticized notion of nature as detached and untouched. Because the Romanticization of nature is so deeply rooted in our collective consciousness, environmental strategies often reproduce the problems they seek to solve. When we view nature as something completely separate, it becomes impossible to come up with realistic solutions of sustainability.

So what can we do? Instead, We must envision a future in which the relationship between nature and culture is not one of constant battle, but of symbiosis. In order to do so, we need to realize we are part of the natural world, tied to the ecological systems that sustain life, while simultaneously recognizing the non-human world – the nature we didn’t create. To create a sustainable reality, we must first work from a place in-between these two concepts: we are nature/nature is outside of us. Although a challenge, this is the only way that a harmonious relationship between nature and culture can be created.

We need to understand the implications, problems and risks of what it means to view nature as something outside or rather separate from our actual place within it. Viewing nature through a lens of detachment becomes extremely problematic, as things seen at a distance have the dangerous potential to become abstract. When we remove ourselves from nature, we simultaneously romanticize it. In this romanticization nature becomes a commodity in constant battle with culture.

By looking at the sublime and the frontier movements, Cronin studies how, in the last 250 years our view of wilderness and nature have transformed from something ‘deserted’ and ‘savage’, to something godly, sacred and exotic. In these ways nature is seen as a cultural invention. This way of thinking exoticizes nature, implanting an ‘untouched’ image of wilderness into the Western Consciousness, while also propagating the idea that nature has died as a result of human interference. This view gets in our way of thinking progressively about a world where humans can strive towards a nature we are part of.

Unfortunately this ideology has been carried forward into sustainability practices, with new environmental initiatives springing from the romanticized notion of nature as detached and untouched. Because the Romanticization of nature is so deeply rooted in our collective consciousness, environmental strategies often reproduce the problems they seek to solve. When we view nature as something completely separate, it becomes impossible to come up with realistic solutions of sustainability.

So what can we do? Instead, We must envision a future in which the relationship between nature and culture is not one of constant battle, but of symbiosis. In order to do so, we need to realize we are part of the natural world, tied to the ecological systems that sustain life, while simultaneously recognizing the non-human world – the nature we didn’t create. To create a sustainable reality, we must first work from a place in-between these two concepts: we are nature/nature is outside of us. Although a challenge, this is the only way that a harmonious relationship between nature and culture can be created.

Cover of the book The World Without Us by Alan Weisman (CLICK FOR LINK)

Cover of the book The World Without Us by Alan Weisman (CLICK FOR LINK)

“Wilderness embodies a dualistic vision in which humans are entirely outside the natural… to the extent that we celebrate wilderness as a measure of which we judge civilization, we produce the dualism that sets humanity and nature at opposite poles. We thereby leave ourselves little hope of discovering what an ethical, sustainable, honorable human place in nature might actually look like… Worse: to the extend that we live in a urbanized industrial civilization but at the same time pretend to ourselves that our real home is in the wilderness, to just that extent we give ourselves permission to evade responsibility for the lives we actually lead. We inhabit civilization while holding some part of ourselves _ what we imagine to be the most precious part _ aloof from its entanglements… in all these ways, wilderness poses a serious threat to responsible environmentalism at the end of the twentieth century.” (Cronon 11)

Response #6

Eco-minimalism

Eco-Minimalism: The Antidote to Eco-Bling

by Howard Liddell

“Given that buildings are the point of consumption and of about half of society’s problematic flows of materials and energy, that iconographic design philosophy is an uneasy, if not inconsistent, perspective. Indeed substituting substance by image risks making everything so much worse” (Liddell iv).

Through an accumulated research of over 50 years Howard Liddell has compacted the verdicts of ‘green’ design in a direct and well-organized book. His research has shown that despite various characteristics of these solutions (image, aesthetics, etc.), their impact on the physical environment is made visible through assessment. In many cases it becomes difficult to identify why something has worked but because of the physical aspect of solutions it is easy to distinguish if it has failed to make an impact.

We have all the technology and methods for sustainable building that if assembled correctly can have a real impact. But the problem arises when architects, designers and engineers work in isolation rather than collaboration, and also when their strategies are not researched thoroughly to see if it has worked in the past or not. A research into the past will allow them to prevent making the same mistakes, and more importantly to understand why it didn’t work in the past. What makes this process even more problematic is when governments and guidelines such as LEED support and create incentives for incorporating worthless methods. By incorporating methods such as solar panels, green roofs, living machines, and so on, not only will they fail to save energy, and money, but make things even worse than they are today.

The main point is “to look at lowering the demand for energy in the first place, before getting excited about alternative energy technology on the supply side of the equation” (6). Through a passive design approach or eco-minimal strategies, such as airtightness, passive solar gain (while addressing lighting issues), and minimal heating just to name a few, we are able to save money and reduce the carbon footprint at the same time. Intuitive design and well-applied science in accordance to the cyclical flow of the four elements (fire, air, earth and water) will not only save money and reduce the carbon footprint, but also create healthy and quality spaces. Cyclical flow of elements, such as heat from the sun, means to look carefully at where it comes from, how is it used and where does it go. The key is to ignore complicated assemblies of technologies whenever possible, and to integrate sustainable strategies throughout the building process.

by Howard Liddell

“Given that buildings are the point of consumption and of about half of society’s problematic flows of materials and energy, that iconographic design philosophy is an uneasy, if not inconsistent, perspective. Indeed substituting substance by image risks making everything so much worse” (Liddell iv).

Through an accumulated research of over 50 years Howard Liddell has compacted the verdicts of ‘green’ design in a direct and well-organized book. His research has shown that despite various characteristics of these solutions (image, aesthetics, etc.), their impact on the physical environment is made visible through assessment. In many cases it becomes difficult to identify why something has worked but because of the physical aspect of solutions it is easy to distinguish if it has failed to make an impact.

We have all the technology and methods for sustainable building that if assembled correctly can have a real impact. But the problem arises when architects, designers and engineers work in isolation rather than collaboration, and also when their strategies are not researched thoroughly to see if it has worked in the past or not. A research into the past will allow them to prevent making the same mistakes, and more importantly to understand why it didn’t work in the past. What makes this process even more problematic is when governments and guidelines such as LEED support and create incentives for incorporating worthless methods. By incorporating methods such as solar panels, green roofs, living machines, and so on, not only will they fail to save energy, and money, but make things even worse than they are today.

The main point is “to look at lowering the demand for energy in the first place, before getting excited about alternative energy technology on the supply side of the equation” (6). Through a passive design approach or eco-minimal strategies, such as airtightness, passive solar gain (while addressing lighting issues), and minimal heating just to name a few, we are able to save money and reduce the carbon footprint at the same time. Intuitive design and well-applied science in accordance to the cyclical flow of the four elements (fire, air, earth and water) will not only save money and reduce the carbon footprint, but also create healthy and quality spaces. Cyclical flow of elements, such as heat from the sun, means to look carefully at where it comes from, how is it used and where does it go. The key is to ignore complicated assemblies of technologies whenever possible, and to integrate sustainable strategies throughout the building process.

Response #7

The place of technology

"Reinterpreting Sustainable Architecture: The Place of Technology"

In: The Journal of Architecture Education

by Simon Guy & Graham Farmer

There are many different interpretations of sustainability. The core values and thoughts attach to any single interpretation greatly influences the physical space and its spatial quality. Through an extensive research, Guy and Farmer have categorized six frames of thoughts that are most commonly associated with sustainable design and thinking. What they argue is that while the definition of sustainability is kept loose, vague and therefore problematic, there is in fact a perspective with a very specific set of values that benefits from this “single, homogeneous categorization of green design”. (Guy & Farmer 140) The definition of sustainability that has come to dominate all other modes of thought is described by Guy and Farmer as “the technocist supremacy.”(140)

The Eco-technic logic takes an objective perspective in dealing with the scientific problems of sustainability (global warming and etc.) and through rational science comes up with different technical strategies in dealing with these vast environmental problems. This logic becomes dominating through different standardization strategies such as LEED, and by controlling and influencing the image and aesthetic of sustainability as a whole. What’s more important is that by taking a highly technical, engineered and scientific approach to sustainable design, the social, cultural and political aspects get pushed to the side. These other aspects are usually ignored even though the eco-technic logic itself creates a specific social and cultural space, chooses to concern itself with specific sectors of economy, and looks into a specific categorization or check boxes for approval; an approval that is granted by the standardized and politicized methods for governing sustainable design.

Consequently each competing logic of sustainable architecture is categorized and described by Guy and Farmer through the image of space the logic takes, it’s source of environmental knowledge, the building image, technologies it is commonly associated with, and finally the logic’s idealized concept of place. I will continue to use Guy and Farmer’s research to categorize various design competitions for my work; although sometimes a specific design is likely to belong to more than one category. The design of the Planetarium by Cardin Ramirez for example represents itself with the eco-centric and eco-aesthetic logic but in reality it is closer eco-technical production. Therefore the categorization of buildings isn’t always clear, depending on how the team chooses to represent their image and provide their (at times contradictory) solutions, but the six logics can always provide a way to start thinking about the various frames of thoughts associated to each competition.

‘The Ecotechnic Logic – Building and the Global Place’

Figure 1 Centre Pompidou by Richard Rogers. source: www.richardrogers.co.uk

Based on “rational analysis and policy-oriented discourse” (142), the ecotechnic logic believes that the proper response to global environmental crisis is to integrate high-tech and innovative technology into the construction of buildings. This top-down approach puts all the trust on science and technology, while not paying close attention to various effects of development. Some of their strategies include: insulation, photovoltaics, lighting, passive solar, natural and hybrid ventilation, more efficient air conditioning and other solutions that can be more complex. In the ecotechnical view “success is expressed in the numerical reduction of building energy consumption, material embodied energy, waste and resource-use reduction, and in concepts such as life-cycle flexibility and cost-benefit analysis.” (142)

‘The Eco-centric Logic – Buildings and The Place of Nature’

Figure 2 Earthship Global Models by Mike Reynold. source: www.greenhomebuilding.com

The eco-centric logic aims to go off the grid and transform values associated with the capitalist society and the eco-technic logic. Instead of believing we can address environmental issues through further industrialization, the eco-centric believes that humans as a small part of earth’s community have used up too much of the earth’s resources and the only way to go back to ‘nature’ is to stop treating earth like a commodity. Their romanticized view of nature is derived from systematic ecology, the idea that in nature, its vast connected network of life flourishes by a natural cycle that humans have disrupted. Buildings therefore represent this parasitic nature of our way of life. To be sustainable requires the protection of ecosystems and a nature that humans are not part of (i.e. everything outside of urbanized environments). For building this means we have to rethink all the ways we go about construction and production. “The essential mission of sustainable architecture becomes that of noninterference with nature, the ultimate measure of sustainability is the flourishing of ecosystems, and the fundamental question is whether to build at all.” (143)

‘The Eco-aesthetic Logic – Buildings and the New Age Place’

The eco-aesthetic logic tries to reach out to the heart and consciousness of society by the image and aesthetics of buildings in order to invoke our imagination of the other non-human world. Its ideals are derived from a romanticized view of nature, but different than the eco-centric logic where they imagine a complexity and non-linear dynamic to life, rather than harmonious and balanced ecology. In search of a way to break free from old forms of architecture and culture, and to inspire people through the look and aesthetics of building of this complexity in our universe, the eco-aesthetic buildings take an organic, expressional form full of curves and abstract geometries.

Figure 3. Qatar Convention Center by Arata Isozaki. source: www.dezeen.com

‘The Eco-cultural Logic – Buildings and the Authentic Place

Figure 4 Bharat Bhavan Bhopal by Charles Correa. Source: prestige-singapore.com.sg

The eco-cultural logic recognizes that through standardization and universalization of sustainable strategies the importance of locality is lost. Each place has its own sense, identity, culture and deeply rooted ways of constructing based on local materials and techniques at hand. These particularities that give place a sense of authenticity become threatened and destroyed by “universal and technologically based design methodologies as these often fail to coincide with the cultural values of a particular place or people.” (144) In order to conserve nature with humans as part of its vast network of rich diversity, the eco-cultural logic tries to address the constraints and possibilities of a particular place by an appropriate design strategy. These strategies often involve “re- use of traditional construction techniques, building typologies, settlement patterns… use of local materials and an appropriate formal response to the climate.” (144)

‘The Eco-medical Logic – Buildings and the Healthy Place’

Figure 5 Plummerswood by the Gaia Group. Source: connect.innovateuk.org

The eco-medical logic is concerned with the individual’s health. To have good health is to have a healthy built environment. Various technologies in space allow us significant control over our environment that creates a separation from conditions of our natural habit. This sense of separation along with the intensity of urban life attributes to much of our health problems. These problems mainly formed through stress, affects us both physically and psychologically. So the aim of the eco-medical logic is to “design buildings that meet our physical, biological, and spiritual needs. Their fabric, services, colour and scent must interact harmoniously with us and the environment . . . to maintain a healthy, living indoor climate.” (145)

‘The Eco-social Logic – Buildings and the Community Place’

The eco-social logic believes that the root of ecological problems comes from the visible and non-visible structures of power and control in society. Their response to hierarchical social and class problems is to design communities or design for communities to enable people to live more equally. By changing the social aspect of space they argue individuals will strive to live in harmony and keep in touch with the surrounding environment. Therefore through a humble way of life where work is distributed equally and resources are used as minimally as possible, we will have less of an impact on our environment. “The aim throughout is to construct appropriate, flexible, and participatory buildings that serve the needs of occupiers without impacting on the environment unnecessarily by using renewable natural, recycled, and wherever possible, local materials.” (146)

Figure 6 Kéré Architecture by Burkina Faso. Source: http://www.spatialagency.net

In: The Journal of Architecture Education

by Simon Guy & Graham Farmer

There are many different interpretations of sustainability. The core values and thoughts attach to any single interpretation greatly influences the physical space and its spatial quality. Through an extensive research, Guy and Farmer have categorized six frames of thoughts that are most commonly associated with sustainable design and thinking. What they argue is that while the definition of sustainability is kept loose, vague and therefore problematic, there is in fact a perspective with a very specific set of values that benefits from this “single, homogeneous categorization of green design”. (Guy & Farmer 140) The definition of sustainability that has come to dominate all other modes of thought is described by Guy and Farmer as “the technocist supremacy.”(140)

The Eco-technic logic takes an objective perspective in dealing with the scientific problems of sustainability (global warming and etc.) and through rational science comes up with different technical strategies in dealing with these vast environmental problems. This logic becomes dominating through different standardization strategies such as LEED, and by controlling and influencing the image and aesthetic of sustainability as a whole. What’s more important is that by taking a highly technical, engineered and scientific approach to sustainable design, the social, cultural and political aspects get pushed to the side. These other aspects are usually ignored even though the eco-technic logic itself creates a specific social and cultural space, chooses to concern itself with specific sectors of economy, and looks into a specific categorization or check boxes for approval; an approval that is granted by the standardized and politicized methods for governing sustainable design.

Consequently each competing logic of sustainable architecture is categorized and described by Guy and Farmer through the image of space the logic takes, it’s source of environmental knowledge, the building image, technologies it is commonly associated with, and finally the logic’s idealized concept of place. I will continue to use Guy and Farmer’s research to categorize various design competitions for my work; although sometimes a specific design is likely to belong to more than one category. The design of the Planetarium by Cardin Ramirez for example represents itself with the eco-centric and eco-aesthetic logic but in reality it is closer eco-technical production. Therefore the categorization of buildings isn’t always clear, depending on how the team chooses to represent their image and provide their (at times contradictory) solutions, but the six logics can always provide a way to start thinking about the various frames of thoughts associated to each competition.

‘The Ecotechnic Logic – Building and the Global Place’

Figure 1 Centre Pompidou by Richard Rogers. source: www.richardrogers.co.uk

Based on “rational analysis and policy-oriented discourse” (142), the ecotechnic logic believes that the proper response to global environmental crisis is to integrate high-tech and innovative technology into the construction of buildings. This top-down approach puts all the trust on science and technology, while not paying close attention to various effects of development. Some of their strategies include: insulation, photovoltaics, lighting, passive solar, natural and hybrid ventilation, more efficient air conditioning and other solutions that can be more complex. In the ecotechnical view “success is expressed in the numerical reduction of building energy consumption, material embodied energy, waste and resource-use reduction, and in concepts such as life-cycle flexibility and cost-benefit analysis.” (142)

‘The Eco-centric Logic – Buildings and The Place of Nature’

Figure 2 Earthship Global Models by Mike Reynold. source: www.greenhomebuilding.com

The eco-centric logic aims to go off the grid and transform values associated with the capitalist society and the eco-technic logic. Instead of believing we can address environmental issues through further industrialization, the eco-centric believes that humans as a small part of earth’s community have used up too much of the earth’s resources and the only way to go back to ‘nature’ is to stop treating earth like a commodity. Their romanticized view of nature is derived from systematic ecology, the idea that in nature, its vast connected network of life flourishes by a natural cycle that humans have disrupted. Buildings therefore represent this parasitic nature of our way of life. To be sustainable requires the protection of ecosystems and a nature that humans are not part of (i.e. everything outside of urbanized environments). For building this means we have to rethink all the ways we go about construction and production. “The essential mission of sustainable architecture becomes that of noninterference with nature, the ultimate measure of sustainability is the flourishing of ecosystems, and the fundamental question is whether to build at all.” (143)

‘The Eco-aesthetic Logic – Buildings and the New Age Place’

The eco-aesthetic logic tries to reach out to the heart and consciousness of society by the image and aesthetics of buildings in order to invoke our imagination of the other non-human world. Its ideals are derived from a romanticized view of nature, but different than the eco-centric logic where they imagine a complexity and non-linear dynamic to life, rather than harmonious and balanced ecology. In search of a way to break free from old forms of architecture and culture, and to inspire people through the look and aesthetics of building of this complexity in our universe, the eco-aesthetic buildings take an organic, expressional form full of curves and abstract geometries.

Figure 3. Qatar Convention Center by Arata Isozaki. source: www.dezeen.com

‘The Eco-cultural Logic – Buildings and the Authentic Place

Figure 4 Bharat Bhavan Bhopal by Charles Correa. Source: prestige-singapore.com.sg

The eco-cultural logic recognizes that through standardization and universalization of sustainable strategies the importance of locality is lost. Each place has its own sense, identity, culture and deeply rooted ways of constructing based on local materials and techniques at hand. These particularities that give place a sense of authenticity become threatened and destroyed by “universal and technologically based design methodologies as these often fail to coincide with the cultural values of a particular place or people.” (144) In order to conserve nature with humans as part of its vast network of rich diversity, the eco-cultural logic tries to address the constraints and possibilities of a particular place by an appropriate design strategy. These strategies often involve “re- use of traditional construction techniques, building typologies, settlement patterns… use of local materials and an appropriate formal response to the climate.” (144)

‘The Eco-medical Logic – Buildings and the Healthy Place’

Figure 5 Plummerswood by the Gaia Group. Source: connect.innovateuk.org

The eco-medical logic is concerned with the individual’s health. To have good health is to have a healthy built environment. Various technologies in space allow us significant control over our environment that creates a separation from conditions of our natural habit. This sense of separation along with the intensity of urban life attributes to much of our health problems. These problems mainly formed through stress, affects us both physically and psychologically. So the aim of the eco-medical logic is to “design buildings that meet our physical, biological, and spiritual needs. Their fabric, services, colour and scent must interact harmoniously with us and the environment . . . to maintain a healthy, living indoor climate.” (145)

‘The Eco-social Logic – Buildings and the Community Place’

The eco-social logic believes that the root of ecological problems comes from the visible and non-visible structures of power and control in society. Their response to hierarchical social and class problems is to design communities or design for communities to enable people to live more equally. By changing the social aspect of space they argue individuals will strive to live in harmony and keep in touch with the surrounding environment. Therefore through a humble way of life where work is distributed equally and resources are used as minimally as possible, we will have less of an impact on our environment. “The aim throughout is to construct appropriate, flexible, and participatory buildings that serve the needs of occupiers without impacting on the environment unnecessarily by using renewable natural, recycled, and wherever possible, local materials.” (146)

Figure 6 Kéré Architecture by Burkina Faso. Source: http://www.spatialagency.net

Response #8

The ethical function of architecture

"Space, Place, and Ethos: Reflection on the Ethical Function of Architecture"

In: The Ethical Function of Architecture

by Karsten Harries

While there is an increasing attention paid towards the efficiency and functionality of buildings in regards to sustainable architecture, the problems of locality, the relationship of the architecture and the experience it invokes with its environment goes unnoticed.

By focusing on the experience rather than just the physical attributes of the building, we can create a sense of space that through its spatial narratives communicates with the particularities of location. Regions or human regions as Harries articulates are constructed within broader natural regions. To design ethically is to first study the social and cultural activities that make up that settlement and secondly to understand what characterizes the broader region that surrounds this community settlement. A building beyond being a physical shelter is a spiritual one that must address how the proposed space creates a sense of belonging. A sense of belonging becomes complicated because where we belong in society is in most parts attached to a proximity with necessary activities and attachments of everyday life (ex. jobs, schools, etc.). According to Harries, our way of life with its many tensions is represented by the spirit of architecture, a spirit that he outlines in his essay as the rootless, displaced, homeless, and prisonlike characteristics of modern mobile architecture.

As a result of a mobility that marks our way of life we hardly get the privilege to stick to a particular location that we connect with. Partly because of this mobility there exists architecture that is indifference to its environment (ex. standardized housing, massive developments, etc.). Through an objective outlook towards buildings as functional necessities there is a lack of spatial narratives that speaks with the particularities of location. In this essay mobile architecture is not restricted but exemplified by trailers. Harries describes trailers as spaces that impose on us a sense of detachment with our environment. We are detached with our surroundings and compelled to strictly control our physical shelter, rather than blending and providing a relationship with the environment to create a spiritual shelter.

“The artist may cast his structures into this void, but his heroically defiant gestures cannot transform space into place. If architecture is to restore to us our sense of place it has to break with both functionalism and formalism. A presupposition of this is the recovery of a sense of place.” (Harries 163)

In: The Ethical Function of Architecture

by Karsten Harries

While there is an increasing attention paid towards the efficiency and functionality of buildings in regards to sustainable architecture, the problems of locality, the relationship of the architecture and the experience it invokes with its environment goes unnoticed.

By focusing on the experience rather than just the physical attributes of the building, we can create a sense of space that through its spatial narratives communicates with the particularities of location. Regions or human regions as Harries articulates are constructed within broader natural regions. To design ethically is to first study the social and cultural activities that make up that settlement and secondly to understand what characterizes the broader region that surrounds this community settlement. A building beyond being a physical shelter is a spiritual one that must address how the proposed space creates a sense of belonging. A sense of belonging becomes complicated because where we belong in society is in most parts attached to a proximity with necessary activities and attachments of everyday life (ex. jobs, schools, etc.). According to Harries, our way of life with its many tensions is represented by the spirit of architecture, a spirit that he outlines in his essay as the rootless, displaced, homeless, and prisonlike characteristics of modern mobile architecture.

As a result of a mobility that marks our way of life we hardly get the privilege to stick to a particular location that we connect with. Partly because of this mobility there exists architecture that is indifference to its environment (ex. standardized housing, massive developments, etc.). Through an objective outlook towards buildings as functional necessities there is a lack of spatial narratives that speaks with the particularities of location. In this essay mobile architecture is not restricted but exemplified by trailers. Harries describes trailers as spaces that impose on us a sense of detachment with our environment. We are detached with our surroundings and compelled to strictly control our physical shelter, rather than blending and providing a relationship with the environment to create a spiritual shelter.

“The artist may cast his structures into this void, but his heroically defiant gestures cannot transform space into place. If architecture is to restore to us our sense of place it has to break with both functionalism and formalism. A presupposition of this is the recovery of a sense of place.” (Harries 163)

Response #9

the shape of green

"The Sustainability of Beauty"

In: The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design

by Lance Hosey

Lance Hosey argues that a sustainable design that is purely technical (ex. energy efficient), but pays no attention to aesthetics of design, is in fact not sustainable at all. If a design cannot appeal to our senses then it will not last. This is not a superficial call, but an integrative perspective that molds shape, form and function with a vision of the final appeal. In other words a sustainable or green design should not merely be covered up and decorated because it would otherwise be ugly, but be developed with a vision of an aesthetically pleasing form from the beginning of the process. For example a building can take a shape and form that will save energy by making the most use of sunlight when it needs it and avoiding it when it’s a nuisance, but before the designers create the deformation there needs to be a conceptual vision of an appealing building in mind.

Indeed what I have noticed throughout the design competitions is that a technical approach to sustainability that focuses most of its attention on performance but is lacking in design, at time merely covering up the site and decorating it, becomes favorable since the functions of the building is sought to outweighs its aesthetical and in fact sensual quality of spaces. A great point that Hosey brings up is that “in both nature and culture, shape and appearance can directly affect success and survival. From a single cell to an entire planet, much of nature can be described in geometry alone.” (Hosey 26) For the scent of flowers, colors and textures of feathers, and many other sensorial characteristics of our planet’s landscape and creatures, account for their survival in the long run. “If it’s not beautiful, it’s not sustainable. Aesthetic attraction is not a superficial concern – it’s an environmental imperative.” (30)

Another important point by Hosey is to consider the object in its broader concept. From a single chair to the house, neighborhood, city, country and social, cultural world of production that goes into it. In other words everything is connected. Too many times a technology, such as solar wall for example is perceived as sustainable, because through a single function it preserves energy in the long run; however no attention might be paid to its production, transportation, its presence and arrangement in a particular location, or the general appeal as a result of the proposed design. Most importantly The Shape of Green shows how the shape or sensorial attributes of design can make up a social, cultural and economical sustainable design. His book directs designers towards an effective aesthetical design for an object to a space through “a clear set of principals for the aesthetics of ecology.” (34)

“Reversing the devastation of nature requires reversing the devastation of culture, for the problem of the planet is first and foremost a human problem.” (34)

In: The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design

by Lance Hosey

Lance Hosey argues that a sustainable design that is purely technical (ex. energy efficient), but pays no attention to aesthetics of design, is in fact not sustainable at all. If a design cannot appeal to our senses then it will not last. This is not a superficial call, but an integrative perspective that molds shape, form and function with a vision of the final appeal. In other words a sustainable or green design should not merely be covered up and decorated because it would otherwise be ugly, but be developed with a vision of an aesthetically pleasing form from the beginning of the process. For example a building can take a shape and form that will save energy by making the most use of sunlight when it needs it and avoiding it when it’s a nuisance, but before the designers create the deformation there needs to be a conceptual vision of an appealing building in mind.

Indeed what I have noticed throughout the design competitions is that a technical approach to sustainability that focuses most of its attention on performance but is lacking in design, at time merely covering up the site and decorating it, becomes favorable since the functions of the building is sought to outweighs its aesthetical and in fact sensual quality of spaces. A great point that Hosey brings up is that “in both nature and culture, shape and appearance can directly affect success and survival. From a single cell to an entire planet, much of nature can be described in geometry alone.” (Hosey 26) For the scent of flowers, colors and textures of feathers, and many other sensorial characteristics of our planet’s landscape and creatures, account for their survival in the long run. “If it’s not beautiful, it’s not sustainable. Aesthetic attraction is not a superficial concern – it’s an environmental imperative.” (30)

Another important point by Hosey is to consider the object in its broader concept. From a single chair to the house, neighborhood, city, country and social, cultural world of production that goes into it. In other words everything is connected. Too many times a technology, such as solar wall for example is perceived as sustainable, because through a single function it preserves energy in the long run; however no attention might be paid to its production, transportation, its presence and arrangement in a particular location, or the general appeal as a result of the proposed design. Most importantly The Shape of Green shows how the shape or sensorial attributes of design can make up a social, cultural and economical sustainable design. His book directs designers towards an effective aesthetical design for an object to a space through “a clear set of principals for the aesthetics of ecology.” (34)

“Reversing the devastation of nature requires reversing the devastation of culture, for the problem of the planet is first and foremost a human problem.” (34)